Is it an upper-level English class? Is it a literature and arts journal? Is it a flower that is illegal to pick in Michigan? Piedmont’s literary and arts journal, that is released in the spring of each year, Trillium, manages to be all of those things at once.

“Trillium is Piedmont College’s undergraduate journal of fine arts and literature,” said Dr. Tim O’Keefe, the faculty adviser for the literature side of Trillium. “What’s unique about it is that a number of colleges have literary journals where faculty serve as editors and try to solicit works form professionals, Trillium thus far has been ninety percent student-run.”

O’Keefe is an associate English professor at Piedmont, and also serves as the faculty adviser and professor of the Trillium journal editing class, where students cycle through the submissions of poetry, prose, and potential manifestos to select what goes into Trillium. Growing up, however, O’Keefe was not as literarily inclined as one would think an English professor to be.

“It never really crossed my mind that reading and English classes would be a profession, or that I would want it to be,” O’Keefe said. “I was an economics and Spanish double major, I did zero creative writing in college, it wasn’t even remotely on the radar.”

After studying abroad, learning to play classical guitar, and avoiding a terrible house mother in Madrid, O’Keefe was exposed to a life that separated itself from completing college for the sole purpose of getting a sedentary office job.

“That experience made me feel in such a way that I probably would never had with economics and business,” O’Keefe said. “I started to get back to thinking about what I wanted to do, I remembered how much I always enjoyed literature, reading it, being immersed in someone else’s thought and use of language.”

Once he took some poetry workshop classes and decided that this was a serious passion of his, O’Keefe got his Ph.D. and found himself in the foothills of Piedmont, where the small class sizes and its classification as a liberal arts college immediately drew him in.

“One of the things I was really looking forward to was it’s a small liberal arts college and that’s the kind of college I went to,” O’Keefe said. “I have very fond memories of colleges, even though I majored in the wrong thing, it showed that to me, and provided me with friends that I still rely on.”

In addition to becoming an English professor at Piedmont, O’Keefe was also given the faculty adviser position of Trillium. The journal originated with Dr. Lisa Hodgens, a now-retired Piedmont professor, in 2006. Hodgens originally ran the Habersham Review, which was a journal similar in style to Trillium, but instead featured work from more professional, acclaimed writers. After funding for that journal decreased, Hodgens worked with the deans at Piedmont to produce Trillium, which she named after a perineal flower native to North America.

“Trillium is a small woodland flower that’s native to the Southeast,” O’Keefe said. “I don’t know if I’ve ever seen one, but apparently they’re out there.”

Trillium is not only focused on literature, however. The journal has expanded to include visual media such as paintings, drawings, and other artwork that is selected by student editors that are taking a class similar to the literature editing Trillium class.

“There are two classes that contribute to it, the art side handles all the artwork and the graphic design of the journal,” O’Keefe said. “We’re working on making it more collaborative between the two sides.”

For the editing class on the literature side, tensions rarely run high when deciding on which pieces are worthy of making the cut to final print. However, even when there are those pieces that divide the editors and O’Keefe, the ability to discuss the pieces to understand each individual’s point of view remains at the core of the Trillium class.

“There are some polarizing pieces,” he said. “Some people love it because it’s strange and other wacky things, and for that same reason other students hate it because it’s too pretentious or whatever it might be. For me, those are the most interesting pieces because they bring the students into direct contact with their own preference and editorial biases, it brings it all full circle into talking about what responsible editing looks like.”

Each piece is submitted anonymously, to the point where even O’Keefe doesn’t know who wrote what until the piece is accepted or denied into Trillium. O’Keefe also does not read any pieces before his students do, so that he can be on par with his editing team.

“Even when students come to me and say that they want to submit and want me to look over their work, I say no, because then I would know who wrote it.” O’Keefe said. “We don’t want any personal biases filtering in, we want to try to keep as much integrity in the process as we can.”

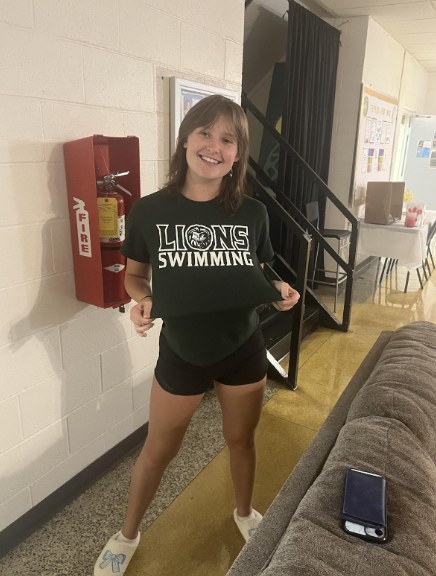

In addition to students being able to submit their own work for the chance to be featured in the journal, one student’s literature piece is chosen by O’Keefe and the student editors to win the Trillium award. The winner is acknowledged at the Trillium release party, where they get a cash prize and the recognition from their peers. Hadley Cottingham, a sophomore English major, won last year’s prize with her piece “lightly”, which came as a surprise to her.

“I was really excited and I didn’t think I would win,” Cottingham said. “I was with all these English majors and accomplished poets. My best friend Sarah Jones was there and when I got it we both freaked out, and it was a great moment for me.”

The deadline to submit to Trillium this year for both literature and artwork is March 4. Any updates will be emailed directly to the students as they come, including all the specific instructions on how many pieces that are allowed to be submitted by one person, which has already been sent out by O’Keefe. Email Dr. O’Keefe at [email protected] with any questions about the submission process. He, along with his class of Trillium editors, is eager to read what you have to submit, and he is ready to see his editors grow as professionals and as people.

“We spend a lot of time getting to our own ideas of qualities versus preference,” O’Keefe said. “We like to think that the things that we prefer are high quality. We make allowances for ourselves sometimes, sometimes we just want to watch a crappy tv show on a Friday night because we don’t want to think too hard. When students start to acknowledge that their subjective take on a thing isn’t necessarily a judgement of merit, that’s when a lot of questions open up. How they experience art in any form, how they perceive them. We get to where we say that, this is my experience on this piece, and yet my experience is just one of potentially billions.”