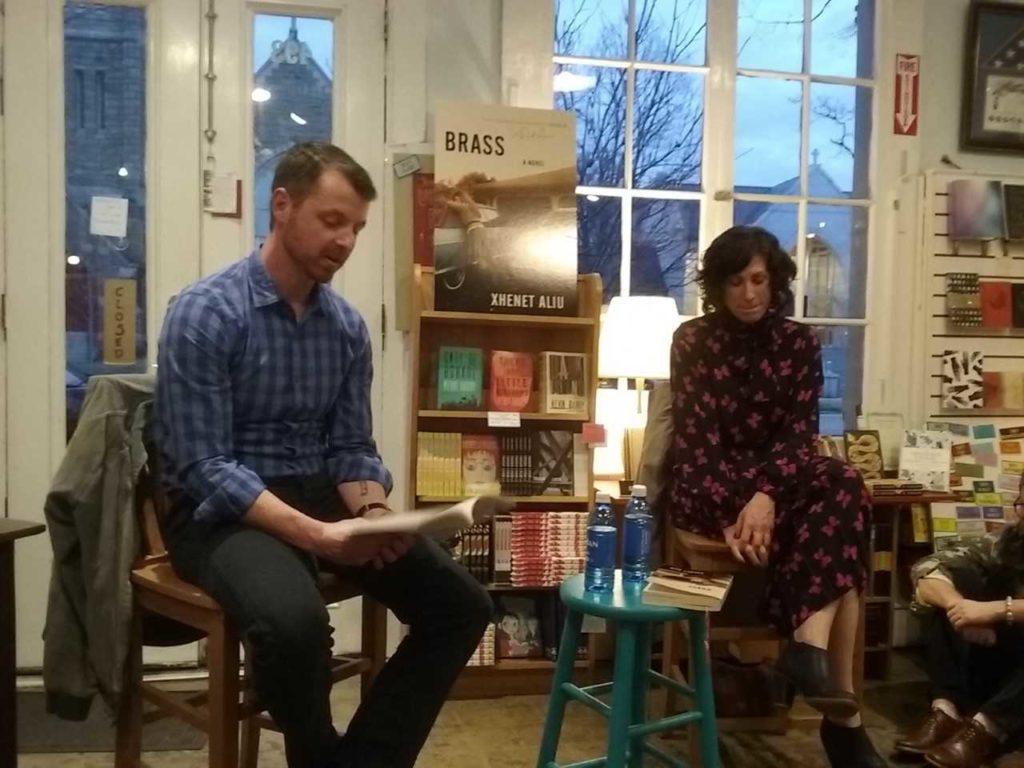

“We realize this is not how most couples conduct a relationship, walking around in silence, staring blankly past each other,” Piedmont librarian Xhenet Aliu said, looking to English professor Timothy O’Keefe. “But lovingly.”

The two writers shared a book launch on Saturday Feb. 17 at Avid Bookshop on Prince Avenue in Athens, packing the tiny store to the shelves with readers, students and friends. Holding court on wooden stools, they answered questions about their work and daily writing practices in the life they share together.

“She is more disciplined than I am,” O’Keefe said. “When she’s in that groove it’s pretty consistent, and it’s always a morning thing. We joke around about… ignoring each other in the morning.”

O’Keefe’s second collection of poetry, You Are the Phenomenology, out next month on University of Massachusetts Press, and winner of the Juniper Prize for Poetry, is dedicated to Aliu. She is credited with the cover photograph of laundry strung across the sky in black and white. Aliu’s debut novel, Brass, was released earlier this year to rave reviews in The Boston Globe, O, the Oprah Magazine and The New Yorker, to name just a few.

“It turned out that there was a wider market than I had originally anticipated,” Aliu said. “Part of it is just timing. This went out (to publishers) in 2016 when the elections were all over the news and we were talking about things like class disparity that we hadn’t in a long time.”

Brass’s parallel narratives, a mother’s and a daughter’s, are set in Aliu’s hometown of Waterbury, Connecticut, a struggling town in a wealthy state, consistently ranked lowest on the list of places to live and work in America.

“It turned out people were really interested in that particular setting,” Aliu said. “Waterbury attracted a lot of immigrants because there was work in the factories, until there wasn’t anymore.”

Aliu said she wanted to complexify the existing narrative about her hometown and the people who live there.

“There wasn’t a whole lot of fiction that I was encountering that dealt with lower income and working-class people in a way that let them keep their dignity and still have complete lives,” Aliu said. “I wanted to say, ‘OK, what happens if you already live in a place that has been called the worst place on earth. Can you still somehow thrive? Can you still have dreams?’”

The popular narratives separate blue collar workers, immigrants, even women, from one another as if they are concepts, Aliu said, instead of individuals with human concerns.

“People tend to cling to these identities that really may not signify very much at all,” Aliu said. “Assigning value based on a completely incidental trait, such as where you were born, or your ethnic background, is I think pretty dangerous. And it’s one of the reasons people scapegoat immigrants, because they think, ‘You’re not one of us. You don’t belong here.’”

Brass, a book about working-class immigrants in a failing factory town, proved relevant in 2018. But Aliu’s friend and fellow Piedmont librarian David Gibbs said she has explored these themes for years.

“She’s been writing this book off and on for a decade,” Gibbs said. “It’s fortunate and unfortunate, that the immigration issue is so hot right now, and that there is an insightful writer to humanize them, for people who haven’t had an opportunity to consider them as people and as fellow humans.”

Aliu’s partner, O’Keefe, is less overtly political in his poetry. But he said that poetry, as a marginalized art form, is political in itself.

“Why it gets marginalized I think is an interesting dilemma,” O’Keefe said. “It comes down to our relationship to language, and how we use it against others. And poetry tries to point out the flexibilities of how language is used and all the intricacies of it.”

Some of his students, O’Keefe said, have had little exposure to poetry, so they don’t know how to approach it. He said the more interesting part is that they seem to distrust poems.

“When a poem is difficult, it must be because the poet wanted it to be difficult,” O’Keefe said. “There’s this suspicion that the poet likes your confusion, that it’s this power trip for them.”

There is likely a link between the political climate and the kind of language we choose to surround ourselves with, O’Keefe said, and the kind of language we shut out because it’s unfamiliar or because it’s saying something we don’t want to hear.

“In the case of poetry, not even wanting to think about why your perspective or your expectations for language are coming up short,” O’Keefe said. “Instead of questioning your own expectations or your own experience, you just point the finger at the other and say, you’re trying to make me feel this way and I won’t let you.”

It is this feeling, O’Keefe said, that poems are elitist or condescending, that makes people get mad at poems.

“They think that poems are trying to attack them or make them feel inferior, so they read defensively,” O’Keefe said. “Of course, you can read the news and think it’s trying to make you feel bad. Or I can talk to students about white privilege and they think I’m trying to make them feel bad, as opposed to just talking about systemic pressures over the course of many decades.”

Aliu said even she feels a certain insecurity when reading and discussing her partner’s poetry.

“I don’t feel secure in the language of talking about poetry,” she said. “I kind of feel like one of your students in that sense. I have emotional responses without the language to discuss it.”

Whether through narrative or verse, both writers are challenging readers to think about the words we use to form our personal ideologies and to label those that differ from our own.

“It’s an interesting point of orbit with language at the center,” O’Keefe said. “How we confront it, how we use it, either in support of or sometimes against others.”