Best Column (1st place) from the Georgia College Press Association.

I tried to kill myself in the fifth grade. It didn’t work.

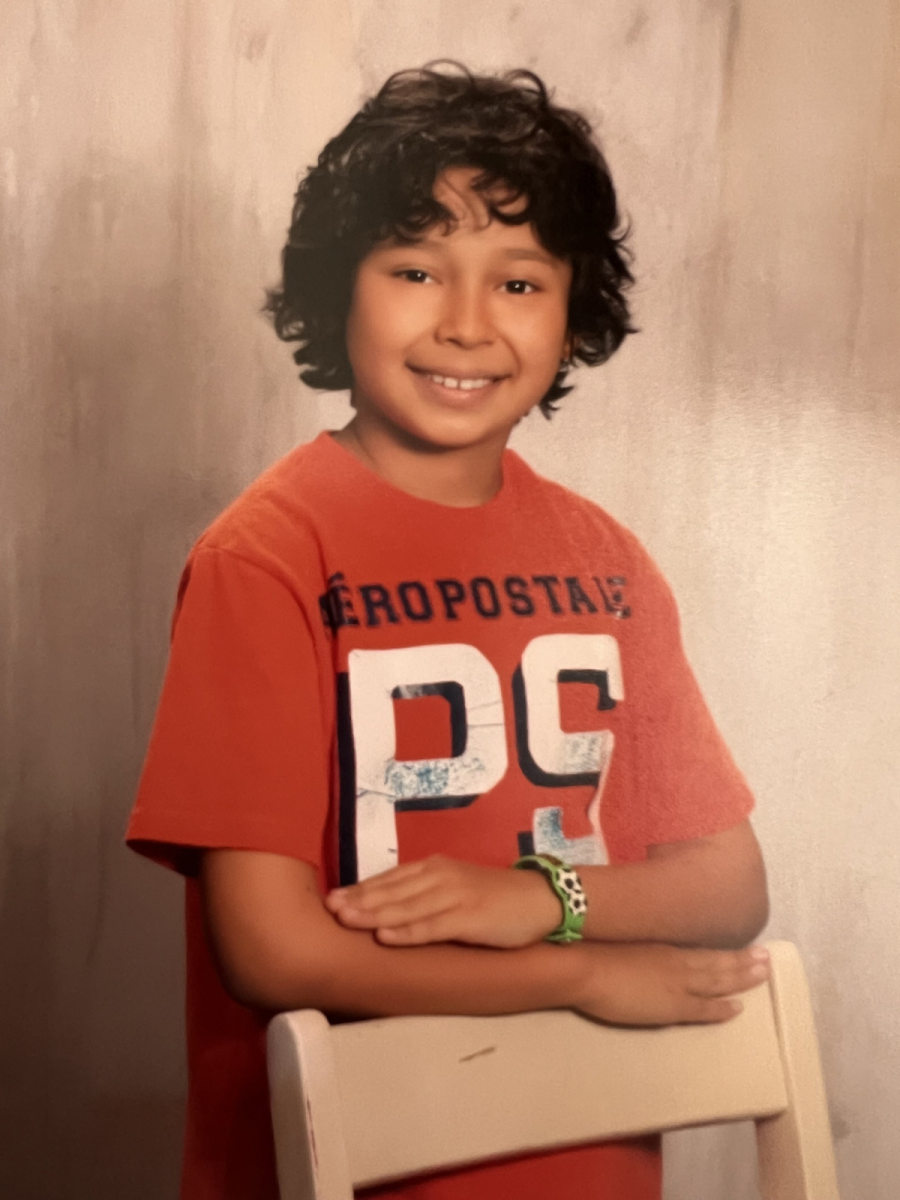

I was 10, and never got in trouble. I was a goody-two-shoes, a teacher’s pet, an extreme rule follower. I earned excellent grades without trying and was always the favorite among teachers. I was the epitome of a gifted kid.

One day I got caught passing notes with my best friend. We wrote some not-nice things about other students in the class. My teacher caught us and held us after class. She told us that she planned to call our parents and inform them of our misbehavior. We’d expect them at the school after lunch.

I was distraught. You would never believe how hard I was crying at the lunch table with all my friends. My mother always told me how important my grades and behavior were. I could not bear to look her in the face. She would be so disappointed in me. I decided I did not want to go through that experience.

So I tried to kill myself at the lunch table.

Yes. Right there, at that moment, at the lunch table.

I tried choking myself. Of course, I didn’t know that even if I did succeed, I would just pass out and start breathing again. My friends tried to stop me, but I ended up stopping myself. Every time I got close to losing my breath, I instinctively released my hands from my throat. This lasted for 28 minutes — the entire lunch period. When the bell rang, I stood up and awaited my doom.

Imagine watching a fifth grader so terrified of disappointing their teachers and parents, that they tried to kill themselves. The pressure of the gifted kid hit me at such a young age. The inch of imperfection drove me beyond drastic measures. Although I can look back and laugh at the absurdity of my suicide attempt, the issue is very real. Gifted students often struggle with mental health issues, and some do successfully end their life.

Eleven years later I still remember that moment vividly and live with the effects of being a gifted kid.

Burnout, anxiety, fear of failure and fear of disappointing others still live with me after I was labeled a gifted kid at such a young age. Many others share these feelings. I believed that making a mistake wasn’t an option for me, and not a natural part of growing up. I felt I would be defined by the mistakes I made.

That day I walked out of the cafeteria to my teachers standing in front of me, not my mother. They all saw my dried snot and tears and reassured that I wouldn’t get in trouble. They did not even call my mom. They laughed and brushed it off. I was relieved, but still shaken.

The “gifted kid” label is a deceptively dangerous title to give to a child that picks up material quicker or is more well-behaved than others. The way we approach the “gifted kids” needs to be changed. We need to teach them that not only is it OK for them to make mistakes, but it’s expected that they make mistakes.

Although I can laugh at my story now, I fear for the current 10-year-old who is on the verge of collapsing under the pressure of being perfect. Their story might not end humorously.